William Housty‘s grandparents taught him the sacred obligation of getting ready for the salmon’s arrival every year. Earlier than the primary silver flashes appeared within the creek, his grandfather — following the knowledge handed down from his personal elders — would clear woody particles, thrust back seals, and perhaps even fell just a few bushes to make sure a waterway was prepared.

“They saw it as their responsibility to roll out a red carpet for the salmon because of their immense importance to us,” mentioned Dúqva̓ísḷa William Housty, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation of British Columbia’s central coast.

This follow ensured that the salmon, the ecosystem and their neighborhood may thrive collectively, mentioned Housty, who’s director of the Heiltsuk Built-in Useful resource Administration Division (HIRMD), which manages assets of their conventional territory.

On supporting science journalism

In the event you’re having fun with this text, take into account supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you’re serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales in regards to the discoveries and concepts shaping our world at present.

Welcoming the salmon is only one instance of the way in which the Heiltsuk’s ancestral legal guidelines, or “Ǧvi̓ḷás — a set of principles centered on respect, responsibility, reciprocity and stewardship for all sentient beings — have shaped their interaction with their environment.

Now, the Heiltsuk are using traditional knowledge in concert with modern scientific approaches to monitor wildlife, count salmon, and maintain the health of waterways in their traditional territory. From the outset, the HIRMD stewards decided that Ǧvi̓ḷás would guide how they managed their resources, as well as influence how they would work with other government offices, industry or other outside parties.

This has led the Heiltsuk to braid relatively new techniques, like DNA analysis, with ancient ones, like the use of traditional fish weirs, so they can study — but not impact — the ecosystem. Their work has revealed shifting bear habitats and climate change impacts on salmon. Both have led to increased protections for creatures that are critical to the ecosystem.

“We’re going again to the worth system that our ancestors carried out for hundreds of years,” Housty told Live Science. “In our eyes, it’s for the betterment of all the things.”

A Symbiotic Relationship

The Heiltsuk have lived in the diverse coastal rainforests, islands and marine areas of their traditional territory for more than 14,000 years. Over that time, they passed on ancestral knowledge of how to care for and enhance the natural resources they depended on.

In the mid-1800s, however, the British colonial government asserted control over Indigenous lands. In the following decades, deforestation, overfishing and pollution led to a marked decline in the richness of life.

“Have a look on the market — it is stunning,” Housty said, pointing to the shimmering ocean water west of Bella Bella, the central community of the Heiltsuk Nation. “However if you go underwater, it is a completely different story — so many assets have been depleted to the extent that a few of them have gone extinct.”

For instance, commercial fishing has led to drastic declines in Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus) and Northern abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana). Some salmon that once thrived in the rivers and streams around Bella Bella have disappeared.

A view of the Nice Bear Rainforest, seen from a mountaintop above the Heiltsuk First Nation city of Bella Bella, British Columbia, Canada.

John Zada/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Authorities officers, forest firms and academia have their very own agendas, mentioned Q̓íx̌itasu Elroy White, an archaeologist who works half time for HIRMD. “It was often based on greed, commercial enterprise, and academic privilege and perspective,” White mentioned.

This contradicted the Heiltsuk way of life in concord with the atmosphere, through which they take solely what they should guarantee a sustainable provide of assets for future generations.

Defending the bears

For a lot of a long time after colonization, federal and provincial businesses managed fishing quotas, logging operations and different useful resource administration selections that straight affected the Heiltsuk. Nevertheless, that began to vary within the Nineties, and a small workforce of Heiltsuk started doing subject assessments on the well being of the streams and salmon within the Koeye watershed, 34 miles (55 kilometers) southeast of Bella Bella. The workforce introduced knowledge to the Heiltsuk land use committee, which might use that info to craft conservation administration plans. One key aim was to guard grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) habitat.

If “you protect grizzly bear habitat, you’re protecting black bear habitat, wolf habitat, deer habitat and many other species,” Housty mentioned. “When you have lots of bears, it means you have a healthy ecosystem.”

The Heiltsuk started monitoring bears straight within the Koeye watershed within the early 2000s.

The variety of Heiltsuk researchers grew, and in 2010, the Heiltsuk fashioned HIRMD. That very same 12 months, they partnered with College of Victoria wildlife scientist Chris Darimont, who can be the science director on the Raincoast Conservation Basis, and his graduate college students. The tutorial workforce expanded the monitoring throughout a bigger area of the Heiltsuk territory in a approach that aligned with Heiltsuk values.

“A lot of the concepts were relational in that they were about how wildlife were like relatives to the Heiltsuk,” Darimont mentioned, “and ought to be treated accordingly.”

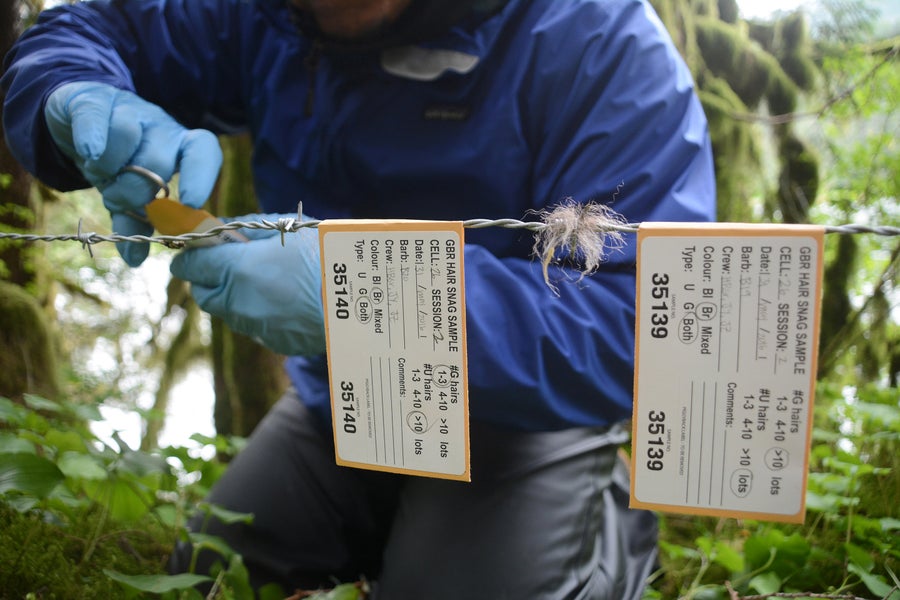

As a substitute of catching grizzlies, sedating them and attaching monitoring collars to them, which ultimately fall off, the researchers took a wholly completely different method: They created knee-high salmon-scented bear snares — barbed wire corrals round bushes — and set 30 within the Koeye and greater than 100 all through the bigger research space. Lured to the odor, the bears left hair samples, and the Heiltsuk used their DNA to trace their actions. The noninvasive technique did not disrupt the bears’ standard habits; the bait offered no rewards to the bears, so the grizzlies did not turn out to be depending on the snares for meals.

A subject researcher collects a hair pattern for a DNA research about grizzly bears within the Nice Bear Rainforest, in British Columbia, Canada.

John Zada/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Monitoring the bears, accumulating scientific knowledge and collaborating with educational scientists are proving important to the Heiltsuk’s involvement in administration selections, Housty mentioned. Traditionally, once they did not have the scientific assets, authorities organizations managed the administration of pure assets. “It is our partnerships and the science that has really given us the legs to stand on for joint management,” Housty mentioned.

The collaborations have helped the Heiltsuk establish bears on islands exterior their conventional vary and have pinpointed essential corridors the bears use to maneuver between feeding areas, in response to new analysis that’s beneath evaluation for publication. Such findings have led to higher safety for bear habitats and can proceed to take action, Darimont mentioned.

The Heiltsuk stewardship ideas usually distinction with dominant government-led conservation approaches, which can recommend that searching grizzly populations is appropriate when the numbers are sustainable. Seeing wildlife as a pure useful resource to be managed by people is wrong and unethical, Housty mentioned. Even a single particular person killed by trophy hunters is unacceptable, he mentioned. “It violates our law regarding respect and reciprocity to the bears,” Housty mentioned.

In 2017, after gauging the broader public’s views and listening to Indigenous views, the British Columbia authorities ended trophy searching of all grizzlies all through the province.

Grizzlies feed on salmon throughout the spawning season, leaving the carcasses, pores and skin, bones and leftover flesh to complement forest soils and feed aquatic invertebrates, which, in flip, assist juvenile salmon throughout their adolescence phases. Due to this fact, the ban on trophy searching did greater than profit the bears; it strengthened the territory’s salmon techniques, Housty mentioned.

Salmon stewardship

Every fall, Howard Humchitt and Lenard Stewart go to among the many rivers on their territory, strolling upstream to test salmon spawning habitats. They’re Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen, employed by HIRMD to tackle many roles, from getting ready for the salmon’s return to monitoring the populations of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) and pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha).

Over time, the watchmen have seen sure forms of salmon diminish. Final 12 months, the watchmen counted 7,000 salmon returning to a specific river system the place they used to rely tens of hundreds. “When our fathers were kids, that same river probably had 100,000 salmon in it,” Humchitt informed Reside Science.

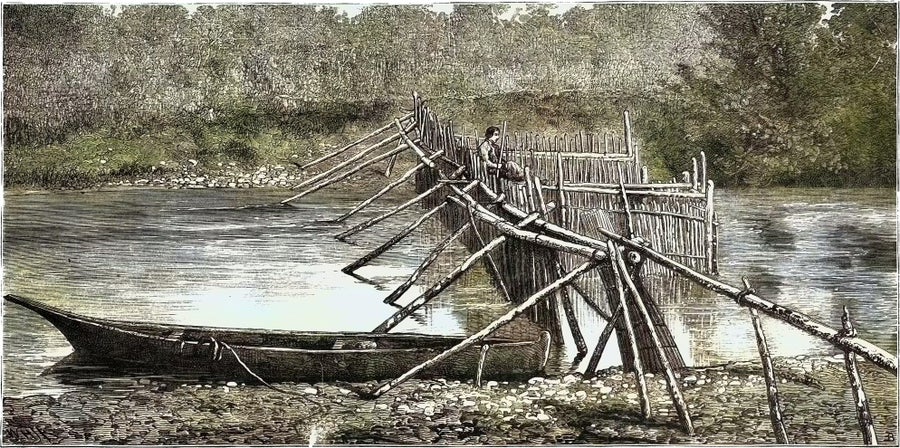

The Heiltsuk traditionally used ancestral applied sciences equivalent to fish weirs. These traps have been product of picket stakes pushed right into a river, which created a semipermeable barrier that directed salmon right into a holding space as they swam upstream. The Heiltsuk additionally used stone fish traps — miniature stone partitions that stretch throughout tidal inlets. Fish swam via excessive gaps within the partitions and, when the tide receded, have been trapped. Nevertheless, the Canadian authorities outlawed such practices within the late Nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a result of officers believed the traps harmed fish shares. However each applied sciences allowed the Heiltsuk to selectively harvest fish, so one of the best fish for breeding may go upstream and spawn. Having dependable fish counts also can stop over-harvesting.

These techniques have traditionally stored fish shares secure, mentioned William Atlas, a salmon watershed scientist on the Wild Salmon Heart in Portland, Oregon. “Prior to the arrival of European colonists, there’s probably about 7,000 or 8,000 years of successful stewardship of salmon harvesting,” Atlas mentioned.

Within the mid-Nineteenth century, nonetheless, the colonial authorities of Canada took over fisheries administration. Since then, overfishing, habitat destruction and nonlocal administration have led to crashes in catches of salmon and herring in British Columbia. A number of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) populations within the province are prone to extinction, and lots of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) runs — migratory populations of a selected river system — are endangered. Atlas, together with Indigenous colleagues, has referred to as for the revitalization of Indigenous fisheries by supporting the sustainable administration practices of coastal First Nations.

An 1882 illustration exhibits a salmon weir at Quamichan Village on the Cowichan River on Vancouver Island, Canada.

Penta Springs Restricted/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Lately, some coastal First Nations, together with the Heiltsuk, have regained a stake within the administration of their fisheries. Accumulating knowledge on their marine assets continues to be essential to the Heiltsuk.

“Knowledge is power when it comes to ecosystems,” Atlas mentioned. “Having numerical values and abundance estimates of how many salmon are returning gives them authority when it comes to co-governance and decision-making.”

To this finish, the Heiltsuk have been monitoring and researching the present state of salmon techniques within the territory to be taught what it takes to maintain them. Additionally they collaborate with scientists to gather knowledge when mandatory. It is logistically difficult to rely sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), as they spawn excessive up in river techniques, sometimes above a lake. So the HIRMD researchers partnered with Atlas and his colleagues to watch these populations, utilizing an method that braids Heiltsuk traditions in salmon stewardship with fashionable science.

Beginning in 2013, the collaborators started utilizing a fish weir comprised of domestically harvested cedar logs to assist them seize and tag round 500 sockeye salmon every year within the Koeye watershed. The researchers rely the outgoing smolts — the younger salmon swimming downstream on their solution to the ocean — after which set up the weir, now product of aluminum, at first of June and start counting the incoming adults. Throughout the salmon’s transient seize, the workforce takes genetic samples from the fish in order that when they’re caught within the ocean, scientists can establish the salmon’s inhabitants of origin.

Annually, the collaborators report sockeye numbers for 5 or extra populations within the territory. The Heiltsuk can then share this info with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), the federal government company that has traditionally set fishing quotas for industrial, leisure and Indigenous fishing in British Columbia.

“That creates a bit of a reversal in the power dynamic that we’ve historically seen, where the DFO is the broker of the truth,” Atlas mentioned.

Planning for the longer term

Searching for future generations and acknowledging people’ function in ecosystems are core ideas of the Heiltsuk’s Ǧvi̓ḷás. Early of their conservation efforts, the Heiltsuk devised a 1,000-year pure assets administration plan.

“Our goal is to live sustainably, so we can ensure an abundance of resources not only for my generation but for those to follow,” Housty mentioned. “We’ve been here since the beginning, and the long-term plan is to stay until the end — if there is ever an end.”

Ǧvi̓ḷás additionally emphasize that people are as accountable for caring for his or her territory as they’re for their very own properties. To uphold their stewardship practices, the Heiltsuk educate their youngsters on their tradition, fostering a reference to the pure world from an early age. The Qqs Initiatives Society, a Heiltsuk nonprofit in Bella Bella, helps youth, tradition and the atmosphere, providing applications to strengthen bonds with Heiltsuk lands and waters.

“We want our youth to feel connected to their territory because it’s an intrinsic part of their identity,” mentioned Cúagilákv Jess Housty, govt director of the Qqs Initiatives Society. “And we want them to love it, because we know if they love it, they will protect it.”

One aim is to exhibit how people can contribute positively to ecosystems. This requires embracing the Heiltsuk understanding that people are usually not separate from their atmosphere. Elders would inform Housty that the Heiltsuk did not personal their territory; it belonged to the animals and fish. That implies that the Heiltsuk have a accountability to maintain the creatures of their territory, William Housty mentioned. “That’s a far different mindset from viewing the land in terms of how much we can take,” he mentioned.

Reporting and journey for this story was supported by the Sitka Basis and the Science Media Centre of Canada.

Copyright 2024 Reside Science, a Future firm. All rights reserved. This materials is probably not printed, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.